RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Exhibition

RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Racing for Thunder was a two-floor retrospective at Red Bull Arts New York, celebrating one of the most uncompromising voices in late 20th-century art. StudioSTIGSGAARD was tasked with creating an environment that could hold the sheer force of Rammellzee’s imagination — a space at once immersive and legible, theatrical yet respectful. Paintings, sculptures, videos, drawings, and ephemera unfolded within a charged architecture that echoed the artist’s own cosmology. More than a retrospective, it became an encounter with a world in perpetual battle against convention, language, and time itself.

Project Size

12,000sf

Location

New York, NY

Beyond the White Cube: Rammellzee Unbound

Rammellzee (1960–2010), often called the “King of the A Line” for his early tagging in Far Rockaway, was a writer, musician, sculptor, and performer whose influence rippled through the downtown scene of the 1980s and 90s. He collaborated with Jean-Michel Basquiat, appeared in Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger than Paradise (1984), and issued manifestos of “gothic futurism” and “Ikonoklast Panzerism” that reimagined language itself as a battlefield. The challenge for the curatorial team and StudioSTIGSGAARD was how to honor this restless, multi-hyphenate practice without reducing it to the calm neutrality of a white cube. The design instead leaned into friction, building a framework that amplified the work’s intensity and invited visitors to step inside the myth.

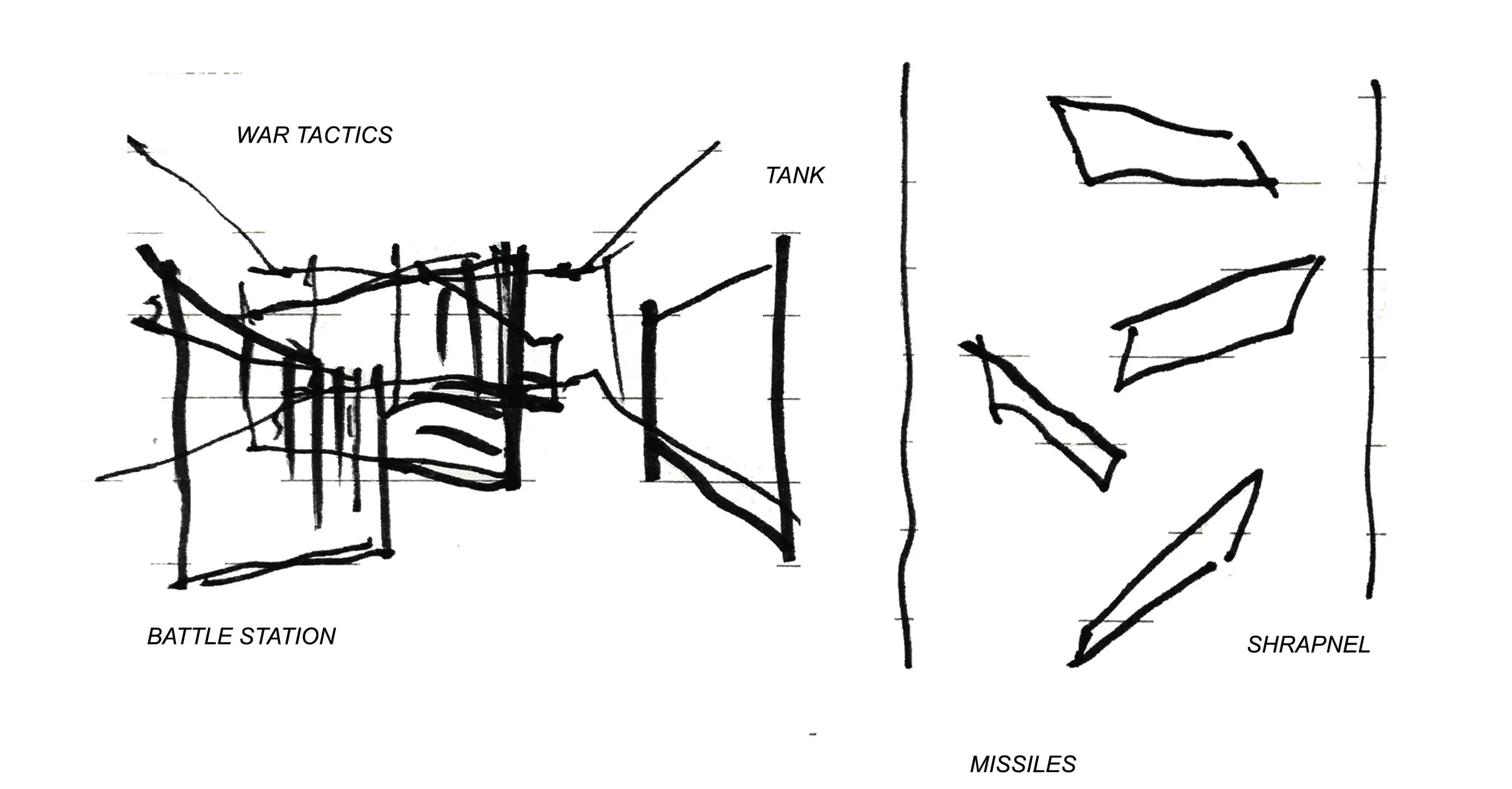

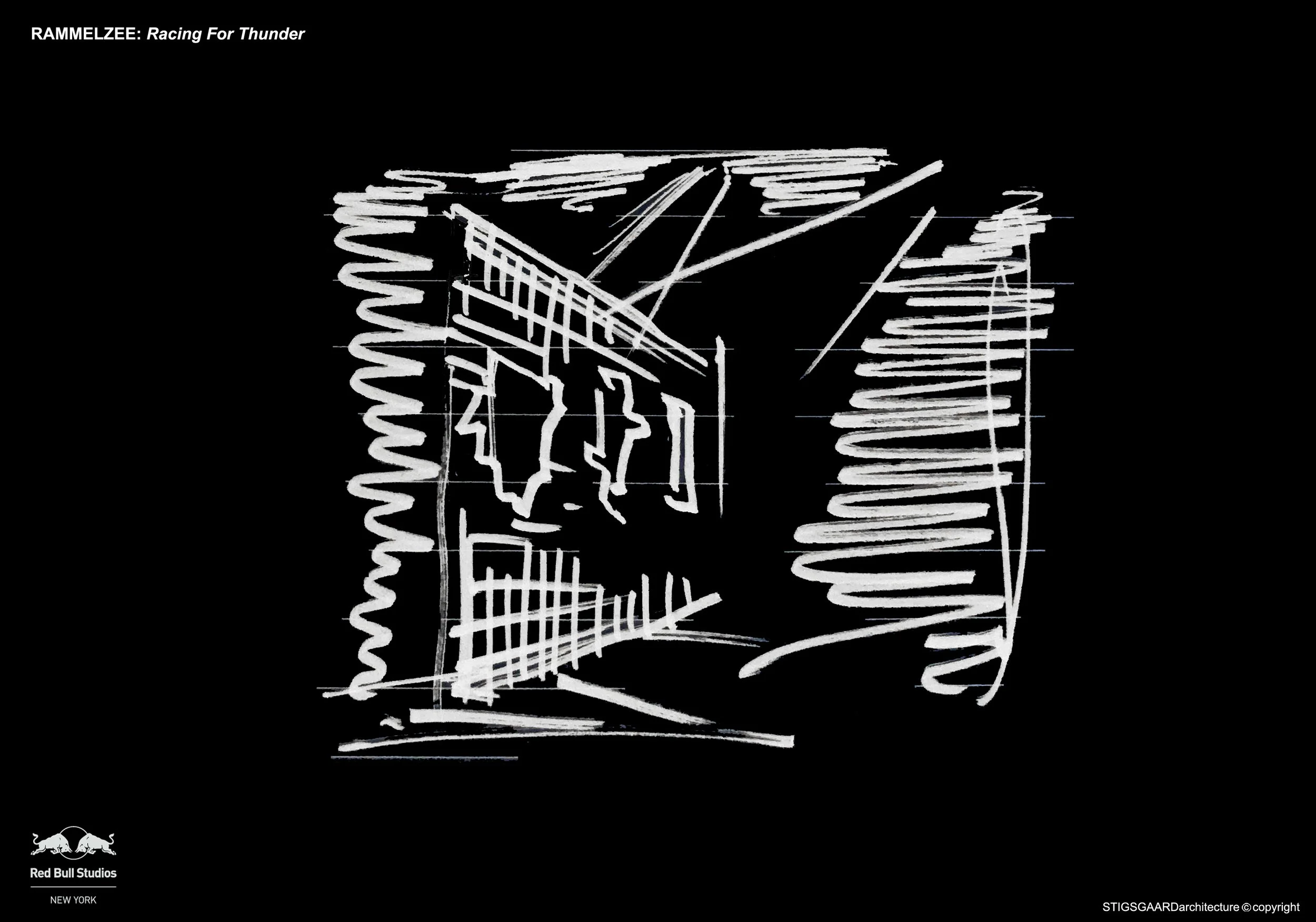

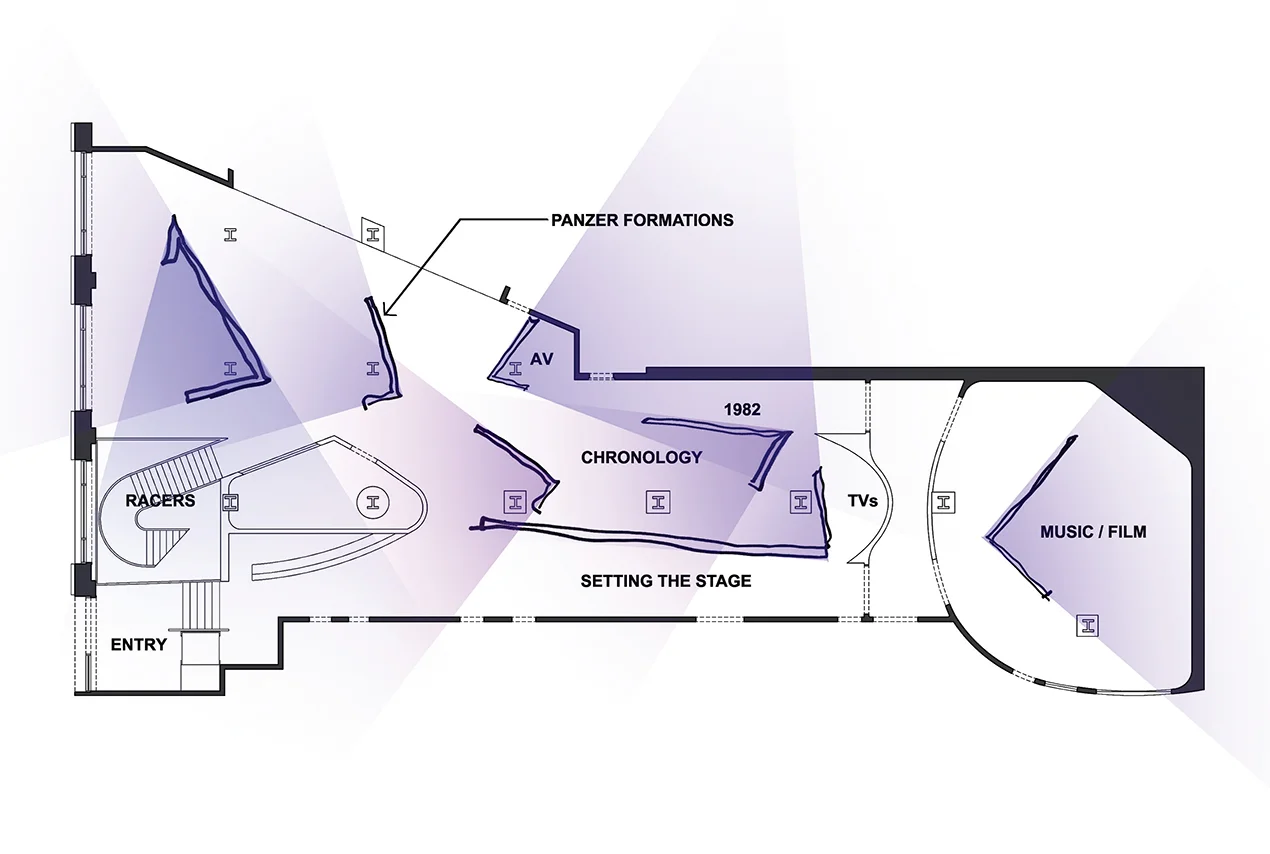

Framing the Battle Station

At the height of his notoriety, Rammellzee retreated into his Tribeca loft, the legendary Battle Station, where he spent twenty years constructing a Gesamtkunstwerk — an evolving world of sculpture, performance, and philosophy. Rather than attempt replication, StudioSTIGSGAARD and curators Max Wolf, Carlo McCormick, Candice Strongwater, Jeff Mao, and Christian Omodeo created an architecture that referenced without imitation. Visitors entered through a compressed tunnel of mesh walls, its irregular apertures evoking both a subway passage and a firing range. The spatial language drew on Panzerkeil formations — tank strategies of strength and vulnerability — to organize the upstairs gallery, while angular vitrives and jagged sightlines mirrored the martial logic of the work. The exhibition became a sequence of confrontations: compressed and released, immersive yet narratively clear.

The Architect’s Newspaper

“Stigsgaard’s design, which was developed in close collaboration with curators Max Wolf, Carlo McCormick, Candice Strongwater, Jeff Mao, and Christian Omodeo, honors the legacy of Rammellzee’s Battle Station, without trying to replicate it, something they felt could not be done by anyone except Rammellzee himself.”

Light, rhythm, and immersion

Lighting was treated as an active collaborator. Upstairs, the galleries shifted from white light to black light, making canvases and sculptures blaze with ultraviolet energy. Rammellzee’s Letter Racers — 26 fighter-plane assemblages mounted on skateboards and cars — spiraled down the stairwell like an alphabet prepared for battle. Downstairs, the ceiling dropped and the space darkened into a cave-like “25th century,” built of mesh walls, shredded tires, and glowing polystyrene formations. Here stood the Garbage Gods — full-scale armored suits fashioned from trash — alongside models, luggage, and finally, the urn Rammellzee designed for his own ashes.

The exhibition ended not with closure but with confrontation: red light piercing through the dark, a pyramid hovering at the center, a Garbage God looming nearby. As Stigsgaard observed, “It’s not about creating a comfortable lighting. You need to be a little bit thrown off.” The result was not simply an exhibition but a mausoleum, a temple, and a battlefield — a space where the artist himself seemed still present, and where visitors could feel the charge of his war against the tyranny of the alphabet.